11 Mar 2019

AWS Explained to Shareholders From a Developer

There has been significant discussion recently around the following revelation in Lyft’s S1:

In January 2019, we entered into an addendum to our commercial agreement with AWS, pursuant to which we committed to spend an aggregate of at least $300 million between January 2019 and December 2021 on AWS services. If we fail to meet the minimum purchase commitment during any year, we may be required to pay the difference, which could adversely affect our financial condition and results of operations.

Many reactions I’ve seen to this post have expressed surprised at this dollar amount and suggested Lyft should build their own data center (which was nicely rebutted here) or switch to another cloud provider.

In addition, AWS CEO Andy Jassy was recently on Mad Money and revealed AWS has a $30 billion run rate. The CNBC article on the appearance notes:

AWS has become a crucial part of Amazon’s overall business. In 2018, the unit generated $25.66 billion in revenue, or 11 percent of Amazon’s total sales, up from 10 percent of overall revenue in 2017. Growth at AWS accelerated to 47 percent last year from 43 percent in 2017.

Most significantly, Jassy readily admitted to constant price decreases over the years in the various AWS product offerings:

“It’s actually really easy to lower prices,” Jassy told Jim Cramer on CNBC’s “Mad Money” on Thursday. “It’s much harder to be able to afford to lower prices.” In the past decade, AWS has cut prices 70 times, he said.

This appearance, combined with Lyft’s S1, have sparked various attempts to value AWS as a standalone business, determine the extent of AWS’ competition, size the total cloud market, etc. Jassy’s comments also have worried shareholders that AWS margins could materially decline.

This post is an attempt to offer some thoughts on AWS spend from a developer perspective. Lost in much of the financial analysis of AWS is how developers use it on a day-to-day basis. This piece of information is important in doing financial analysis because it can offer insights into the costs of switching cloud providers and Amazon’s probability of retaining customers. I’m not suggesting this post could be used to quantify retention rates or market share, but that some of the information may be a good starting point in terms of how financial modelers think about AWS’ business.

As background, I’m a developer who owns my own consulting company and have worked with a variety of clients that have unique AWS setups. Each client has unique tech needs based on their unique business models and growth stage. Each one picked AWS as their cloud provider.

Notably, not a single one has ever seriously raised the issue of AWS pricing or wanting to switch to Google Cloud Platform (GCP), Microsoft Azure or another service. Again, this is solely my experience, but from a developer perspective, many solutions to problems discussed on blogs, at conferences or in person assume that AWS is the default cloud platform and speak about solutions with a specific set of AWS services in mind. This is the strength of the ecosystem at work.

As an example, serverless architectures have recently become quite popular in the developer community. Serverless is a term that means from a cost perspective fees come in when useful “work” is occurring on a server rather than when time is elapsing. As it pertains to AWS, this is the difference between using an EC2 instance (a service that is priced per unit of time depending on the server specs) and AWS Lambda (a service that is priced closer to per unit of work (ex. per request)).

Many developers when they talk about serverless architectures are usually talking about AWS Lambda. It’s very common to hear suggestions to the effect of “And you could write a Lambda task to do such-and-such and then…” AWS has made Lambda easy to pair with a number of its 100+ services, allowing developers to schedule Lambda tasks to occur immediately after file uploads to a specific S3 bucket (its storage service), entry of an item into SQS (its queuing service) or even specific patterns in Cloudwatch (its logging service). Serverless is as much a discussion about AWS as it is the broad idea of paying per unit of work and not per unit of time.

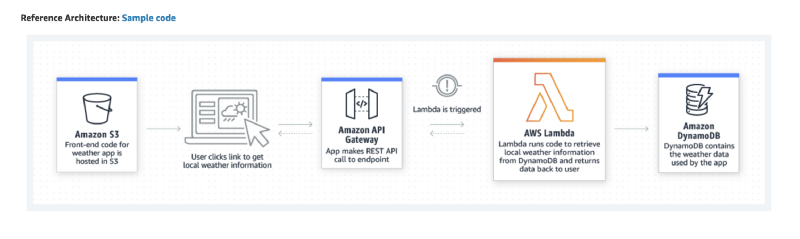

Indeed, AWS is aware of this discussion and plays into the developer enthusiasm for serverless. Let’s look at an example directly from Amazon’s docs on serverless architectures:

To be clear here — to develop a simple weather app, AWS is suggesting pulling in four different AWS services — S3, API Gateway, Lambda and DynamoDB. Code will have to be written for each service and their interactions monitored. The costs will have to be tracked and made understandable for business stakeholders. This setup may even need to be rebuilt several times as the needs of the weather app become more clear.

The paragraph above may seem crazy to you, but rest assured it is actually less crazy than real life. Only four AWS services seems pretty low in the context of apps I’ve worked on.

I make this point to demonstrate that AWS is deeply ingrained in developer culture and becoming more deeply ingrained. It is a staple of how developers think about scaling operations and has entered developer lexicon for the foreseeable future.

Changes in AWS change how developers think about the future and what’s possible. A release of a new AWS service or change to an existing service will trigger thousands of blog posts, training seminars and discussions. As a result, AWS exerts control over the future of software, and by extension its cost, performance and maintainability.

Going back to the example of Lyft, I take issue with analysis that hones in on the $300 million AWS bill when the more important consequence is the complexity associated with this bill. Notice how Lyft never breaks down the spend itself. Is it serverless or server-based? Which AWS services make up the majority of the spend? How much time do Lyft developers currently spend writing code around AWS, and what would be the cost to switch platforms?

As a result, I seriously question analysis that attempts to treat AWS spend as a per-transaction rake for Amazon. Credit card scanners are a commodity and not a core piece of company infrastructure heavily customized by full-time employees.

While companies can and do model AWS costs with good accuracy, what I doubt is modeled nearly as well is the amount of time developers spend customizing and tuning AWS services. I’ve spent hundreds of hours in total reading AWS documentation, blog posts, source code from libraries that use AWS, talking to AWS sales reps and reading AWS message boards. It’s a key part of my job and I’m often hired with my knowledge of AWS specifically in mind.

To underscore that AWS is not a commodity, I want to offer some more details on the costs in developer time of switching to another cloud provider.

Security

The subject of security on AWS is enormous; there is a 74 page whitepaper on it. There are consulting shops that specialize in this subject and charge absurd amounts of money to review your security stack. AWS’ security model requires knowledge of their Identity and Access Management service and the security settings associated with each service (this could be security rules for EC2 or read/write permissions on S3). Rebuilding this security model in another platform would be non-trivial.

Additionally, if your company has government clients, then storing their data in the cloud will require FedRAMP certifications. The AWS docs note:

Cloud service providers who want to offer their products and services to the US government must demonstrate FedRAMP compliance.

Any company running their own data center would have to separately apply for these certifications, which can take in excess of a year to get. AWS is certified for most of its core offerings. Security within organizations, between organizations, between organizations and consumers and organizations and the government is handled in a unique way by AWS, further de-commoditizing it.

Code

I think the average non-developer would be shocked if they searched a company codebase for references to AWS. I’ve yet to see a codebase that does not pull in a variety of AWS libraries and structures significant amounts of code around how these libraries work. Changing all this code would be non-trivial and would definitely require significant re-writes that would pull developers off feature work. This is not find-and-replace.

There is even a robust ecosystem of companies that write code that target the various AWS services and make money off it. Heroku (a Y Combinator funded company that was purchased by Salesforce in 2010) runs many of its servers on AWS. Heroku is the middleman between thousands of companies and AWS. Many code registries tap into AWS to pull down third-party code. These same registries may also rely on Heroku or AWS middlemen. Even if a company switches its own cloud infrastructure to another provider, there is most likely still an AWS dependency in the code.

Developer Workflow

Much of what a developer does day to day in my experience involves using various AWS services. Some examples:

- Reviewing logs or performance metrics to determine the exact circumstances in place when a bug, outage or other event occurred. Developers can use this information to better determine the cause of the event

- Monitoring, downloading or manipulating images, video, audio or other files internal users or customers uploaded into S3 (recall this is Amazon’s Simple Storage Service). S3 also can be used to host entire websites; in this case, the code for the website itself is hosted on S3

- Creating, updating or deleting security rules to protect a company’s digital assets. One example of this is the inbound and outbound security rules on an EC2 instance (said another way, a server) that determine which IP or IP ranges the server can receive data from or send data to. Depending on their seniority or job responsibilities, developers may also be responsible for managing other developers’ permissions on various AWS services (the relevant AWS service here is the aforementioned IAM)

- Configuring services that drive some critical part of a company’s product. AWS has services for machine learning, video games, the internet of things and even satellites. Each has hundreds if not thousands of dials you can turn for your specific use case Jeff Bezos in a 2008 presentation to a Y Combinator batch overviews a number of real world AWS use cases. This video is definitely worth a watch if you’re interested in how Bezos views AWS’ value add (notably, he speaks in depth about Blue Origin’s use of AWS) All of these tasks to some degree require familiarity with the AWS UI and how to achieve certain tasks (this is mockingly known as “click-ops” in some circles). Devs would need to retrain themselves in all these tasks, some of which would no longer exist or exist in very different forms to accommodate a switch.

Additionally, when the UI becomes cumbersome, developers will automate repetitive tasks through the AWS Command Line Interface (CLI), which also requires significant research and practice to get productive in. The cost of a switch from a developer workflow is to uproot how developers interact with the cloud from the browser and within code.

Hiring

In my experiences as both an interviewer and interviewee, AWS has been a key part of hiring. I’m not judging whether this is right or wrong, but rather commenting that interviewers have asked me about it and interviewees have brought it up unprompted. There is an AWS Certification program and I’ve been asked whether I’m certified and seen certs listed on resumes I’ve reviewed. Choosing GCP or Azure as your company’s cloud provider will likely increase the amount of time it takes for an average developer to come in and get comfortable with the company’s cloud setup.

In closing, I want to offer my thoughts on two questions that I think are extremely relevant for analyzing AWS spend and valuing AWS as a business.

Are cloud services a commodity?

Absolutely not. Here’s the definition of commodity from Merriam-Webster (note I’m using the third definition, which I think most applies to economics):

A good or service whose wide availability typically leads to smaller profit margins and diminishes the importance of factors (such as brand name) other than price

I do not believe cloud services in very specific forms with very specific interactions — like the aforementioned weather app AWS services — are a commodity. That said, GCP has tried its best to map each AWS service one-to-one with its own.

I’m not convinced at all that migrating is as simple as consulting this table and writing the migration to go from one service to the other.

Building the aforementioned weather app in the way AWS recommends requires knowledge of four specific services. Yes, these services could be in part replicated with GCP or Azure, but it would take significant time and effort to rebuild it and there’s no guarantee the cost-savings would be significant. For commoditized goods, switching suppliers is trivial. From a code perspective, this is find-and-replace. Switching cloud services is anything but find-and-replace.

Were this not true, I don’t think AWS’ competitors would author comprehensive guides on migrations. If you google “migrate aws to google cloud”, here are the first four results that come up:

Google clearly has skin in the game and has spent time and money promoting the idea that switching is possible.

Is it worth switching from AWS to another cloud provider to save money or starting a company and using another cloud provider?

I did some research on migrating from AWS to GCP and what I found confirmed that this is a difficult undertaking. It’s notable here that complete migrations are not always the best choice for most companies — some companies are diversifying their cloud providers and picking the right tool for the right job. There is no doubt in my mind some Azure or GCP services make more sense than their AWS equivalents for specific companies in specific situations. That said, an 100% migration likely entails spending lots of times in areas where performance and cost improvement would be minimal. Some cloud services to be fair are commodities — how much of an improvement is your company going to get from moving from AWS Simple Storage Service to Google Cloud Storage?

For new companies, I tend to think cost-cutting is less important than product-market fit. Discovering product-market fit is going to be easier with a cloud provider that has a rich ecosystem of libraries and documentation, as well as a large potential talent pool for working with those services.

In conclusion, I think more discussions about margin compression and market share at AWS need to take into account what a critical role AWS plays in the day-to-day life of developers. Margin compression in part assumes that commoditization drives down prices — I’ve tried to rebut the idea here that AWS services are commodities. I’ve also tried to demonstrate that switching providers is non-trivial. When migrations do happen, they may be piecemeal and not complete infrastructure changes.

Modeling cash flows requires making significant assumptions even for the most simple of businesses. AWS is as complicated a business as it is a product, and I would caution current and future shareholders against unfounded assumptions.

Disclaimer: I am an AMZN, GOOGL and MSFT shareholder. I am an AWS, GCP and Azure customer.