25 Nov 2018

EV is Everything

Expected value (EV) is the best mental model I know of for decision making. In this post, I want to explain how EV has begun to guide much of my decision making about the future.

What is EV?

First, let’s back up and give a broad overview of what expected value is and why it’s important. EV per Google is “a predicted value of a variable, calculated as the sum of all possible values each multiplied by the probability of its occurrence.” I interpret this as a wordy way of saying EV is the chance something will happen multiplied by the payoff if it does happen.

A coin flip is the easiest example to start with here, so if I offer you $10 if a coin turns heads, the EV is $5 (50% * $10, the outcome where heads comes up, plus 50% * 0, the outcome where tails comes up).

This coin flip is what I’ve seen many people refer to as +EV, meaning the expected value is positive. This game worst case leaves you with the world unchanged half the time, and best case puts $10 in your pocket half the time. You should play this game forever because the average return is $5.

However, let’s assume it costs $6 to play the game. In this case, the game is -EV; in the win case, EV is $2 in the winning case (50% * (10–6)) and -$3 in the losing case (50% * -6), so total EV is 2–3, or -$1. You should never play this game because the average return is -$1.

In this simple coin flip example, notice the lever we changed to change the EV: what it costs to play the game. Paying anything more than $5 makes the above a -EV game. The other lever we have as the game makers is changing the odds.

The same EV does not mean the same game odds

We can get to the same $5 and -$1 EV above using an unfair coin and different payoffs. If the coin has a 90% chance of turning up heads, a $5 EV is betting on heads with a ~$5.56 payoff ($5.56 * 0.9 === $5). The -$1 EV is charging $5 to play the game with the same payout (0.9 * (5.56–5) + -5 * 0.1 ~== -1). While the EV of both games is the same as in the first example, having a 50% chance of winning $10 is very different from a 90% chance of winning $5.55. Additionally, paying $5 to play the game is different from paying $6 — with higher dollar amounts, a 20% increase in the cost to play will price many people out.

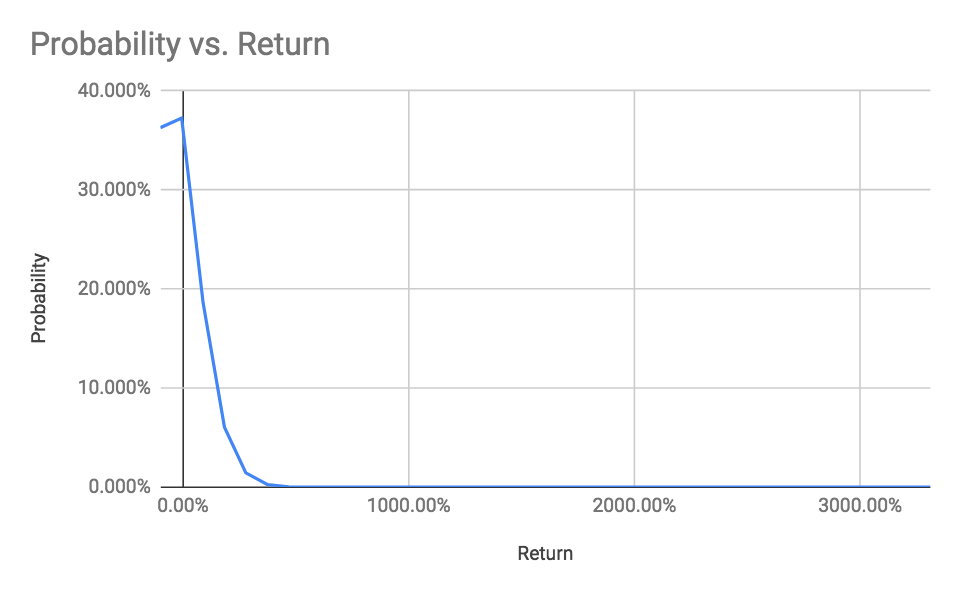

I think this idea becomes even more clear for games with longer shot odds. I was at a casino for Thanksgiving and had to wait an hour for the next available poker table, so I played roulette to pass the time. I was surprised to see the number of players simply placing bet after bet on a single number. Roulette offers a 36:1 payout on a single number hitting when the actual probability is 38:1. This is a negative EV game as a result. Let’s assume you have $190 to invest in 38 roulette turns at $5 each. If you’re comfortable with the 36% chance of losing your investment completely and 37% chance of losing 5% of your investment, there are some huge payoffs at low percentages.

(Note that you can see the spreadsheet I used to make all graphs in this post here).

Moreover, you also have the opportunity to walk away any time you hit the number and reduce that $190 expenditure. To put this in perspective, if your number hits 2 times in a row ((1/38)², or ~0.07% chance), you’ve only put $15 at risk and won $335 for a 22.3x return. You should still never play roulette; it’s a negative EV game (-$10 in the example above).

Let’s contrast this with a more even-odds approach to roulette. The EV is still the same (-$10), but the return profile of investing 5 bucks each on 38 turns looks like this:

I did not see anyone playing this particular roulette strategy, presumably because no one wants to play 38 turns to win or lose up anywhere between 0 and $100 more than ⅔ of the time. It’s more attractive for most players to have a low probability of a huge payout than a near 50% probability of a small payout. I actually asked my brother about this idea and he had a telling quote:

My expectation is that I’ll lose some set amount of money I already decided on or win a lot of money at a casino. Winning a little bit of money isn’t why people go.

But real life is more complicated

As with pretty much every probability example that gets presented to people, the easy response about why it’s non-applicable to real life is that real life is complicated. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Jonathan Bales and others have written about two types of EV, so I’ll overview both. I’m going to call these hard EV and soft EV:

- Hard EV — EV you can confidently calculate that depends on some physics laws that are random (gravity and other forces move a roulette ball to its position — as a side note, Claude Shannon attempted to calculate the position of a roulette ball and bet based on the expected position by using some radar-gun like devices hidden beneath his clothes at casinos — this is detailed in the great book Fortune’s Formula).

- Soft EV — EV based on human events. Sports books, insurance companies, banks and others that price odds impacted by humans back into EVs by seeing what people bet when they offer opening odds on different events

I believe the principles of dealing with hard EV are applicable to soft EV, as long as we admit that our attempts to price soft EV accurately are going to fail. When those attempts do fail, we can use the information gained to price EV more accurately next time. My recent post on Mastermind explores this idea. Moreover, failed attempts to price EV can lead us to pursue +EV generating projects, which is at the heart of the next idea I want to discuss.

Fight for every last scrap of EV

Anyone who has played casino games has definitely done the thing where you go “If only that thing didn’t exist, this would be a great game.” This thought is really just expressing that casinos always do at least one thing in games they offer that makes the game -EV. This is the green 0 and 00 in roulette, the rules around when the dealer hits in blackjack, the programming logic in when slot machines pay out, etc. Casinos are acutely aware of this fact and will actually offer scraps of EV to high rollers or improved odds when they first open.

So, if a small change in odds or payoffs make hard EV games worth playing, I think the same is no less true for soft EV. As someone who has been around start-ups the majority of their career, I have come to believe this is the only thing start-ups do; continually search for +EV activities.

Let’s consider a simple start-up that sells widgets to OEMs that make some part of manufacturing more efficient (maybe it’s an IoT device with machine-learning capabilities or something). The company may estimate there is a 60% chance some big tech company comes in and manufactures the devices for 30% cheaper. They then can start to price how much they should raise in capital to get their devices to be 30% cheaper.

To continue this example, the company could also decide to try to move the goalposts on the 60% chance. They could partner with a big tech company and build in contract language that prevents them from manufacturing competing devices; they could create their own operating system or hardware to make the device harder to replicate; they could decide to migrate out of the widget business because raising capital is too expensive relative to their EV guesstimate.

Just like small changes in casino odds make the games worth playing, start-ups making small changes completely change what is +EV and what is -EV. With soft EV, human actions can wildly change odds and payoffs, so in my mental model I equate new projects and strategies at start-ups to casinos changing the odds and payoffs. From a career perspective, how well start-ups manage EV is how I evaluate whether I want to stay or go; if the odds are continually moving toward a place where the game is worth playing, stay; if not, go.

But then how do you evaluate how people manage EV?

Drop your state-of-the-world evaluations for first principles, especially for long-shots

There’s a story Nassim Nicholas Taleb tells often about how he was at a meeting where traders at his firm said what they thought would happen in the market. Taleb expresses his opinion, and one of his colleagues ask why his portfolio isn’t positioned that way. Taleb responds that what he thinks is irrelevant; all that matters is what the market is mispricing.

I think a reasonable approach to evaluating soft EV — and how people / companies manage it — is to 1) forget what you think you know about the opportunity associated with EV and 2) try to price it from a first principles perspective. (1) improves the odds you stop working off a false collection of EVs. (2) forces creation of a new collection of EVs.

Doing both 1) and 2) may lead to surprising conclusions, which leads me to my next point; unpopular stuff is most likely to be mispriced.

When in doubt, prefer low information EV to high information EV

I remember in grade school social studies learning about the concept of the catch-up effect. The catch up effect says that developing countries will grow faster than developed countries because there are easier gains to be made for the developing countries. A developing country for instance may realize a huge benefit from an infrastructure project that connects two cities; a developed country will have less of these opportunities because that same project was already completed. That infrastructure project may be a percentage point or more of GDP growth for the developing country. The developed country has no comparable way of boosting its GDP, so the developing country is likely to catch up in standard of living, median income, etc. over time.

I think there is a real catch-up effect that exists for “cold” versus “hot” industries. Cold industries are what I consider to be businesses that are not getting attention from the media and very few people are playing in. You are unlikely to find lots of white papers or blogs on it online. In order to find information, you are probably going to have to read forums or maybe even (gasp!) pick up the phone and call someone.

Hot industries are going to be reported on by most tech blogs, have a lot of capital coming in and have highly trained players that are pricing EV like their career depends on it. There are probably a few dozen best-selling books that talk about how the future is going to radically change because of Industry X.

Cold industries are low information industries precisely because they’re “cold” — not popular. Hot industries are saturated with market entrants and information because they’re hot. Low information means more mispricings, because information is the only way we can calculate EV. Without information, we don’t know payoffs or probabilities.

When viewed this way, I think the catch-up effect of cold industries relative to hot industries is real. I believe it’s a strong argument for playing in cold industries. When I’ve argued this point, I’m often told that I’m a contrarian. I actually think that’s an unfair characterization, because contrarian implies that you just like choosing the opposite way the crowd is going. Instead, I think letting EV serve as a mental model for decision-making leads to contrarian viewpoints. Having contrarian viewpoints is a goal worth pursuing because the future can and will have moments where low-information, cold industries become high(er) information, hot industries.

EV is everything because the future is uncertain

Being told you’re a contrarian is a good sign you’re pursuing a EV+ opportunity. We already know the world does not price EV perfectly (that casino was super-crowded on Thanksgiving no less) and has a built-in bias for what’s hot at the moment.

EV+ opportunities are easier to come by in low information industries because there are fewer tools to know payoffs or odds. Said another way, it’s easier to scrap for EV because there are more scraps. When the future turns in a “crazy” way (or just a way the crowd didn’t expect), cold industries are more likely to rise and hot industries to fall because the crowd predicted something that did not happen. The contrarians are then better positioned for the future; the contrarians thus become what’s hot; and the cycle continues.

Investor Howard Marks said in a recent podcast with Tim Ferriss that knowing where we are in the investment cycle is among the keys to calling the market correctly. Just like the investment cycle (boom and bust, high and low leverage), the EV cycle (hot and cold industries, high and low information) is part of the world we live in.

I’m not certain what the future holds, but I know an EV-based view of it will lead to different conclusions than alternatives.