27 Jan 2018

Decision Trees Introduction (ML Series, Part 4)

In my continuing attempt to automate as much as of my Daily Fantasy Sports lineup creation as possible, I’ve been exploring decision trees. I realized this technique might be valuable after listening to my thought process as it relates to fantasy sports. Generally, I’ll ask myself questions like “Has this player broken 10 rebounds the last 2 games?” or “Is this player consistently getting over 25 minutes per game?”. In addition to removing bias, a decision tree should ask better questions, improve given more data and generate insights over key features in data.

I want to start off with the simplest possible example I can think of for a decision tree. I’ll use this example as an opportunity to explore the sklearn.tree module. In a future post, I’ll review in depth how I constructed my DFS basketball decision tree, but you can check it out here if you’re interested.

In Part III of my ML blog series, I reviewed how a neural network could be used to classify some data where only one feature mattered. A similar example here I think will be illustrative. I often find it easier to make the example as close to real as possible, so let’s assume we have data on a group of basketball players, and we want to label them 0 if they scored under 20 points and 1 if they scored over 20 in a game. The three features in the data set are minutes, age and height; let’s assume only minutes matters. Below is a simple decision tree with a fake dataset:

You can see in the code snippet above that tree.DecisionTreeClassifier ships with a feature_importances_ that lists the weight of each feature. Because minutes is the only feature that matters, it’s assigned a weight of 1.0, while the meaningless age and height features have a weight of 0.0.

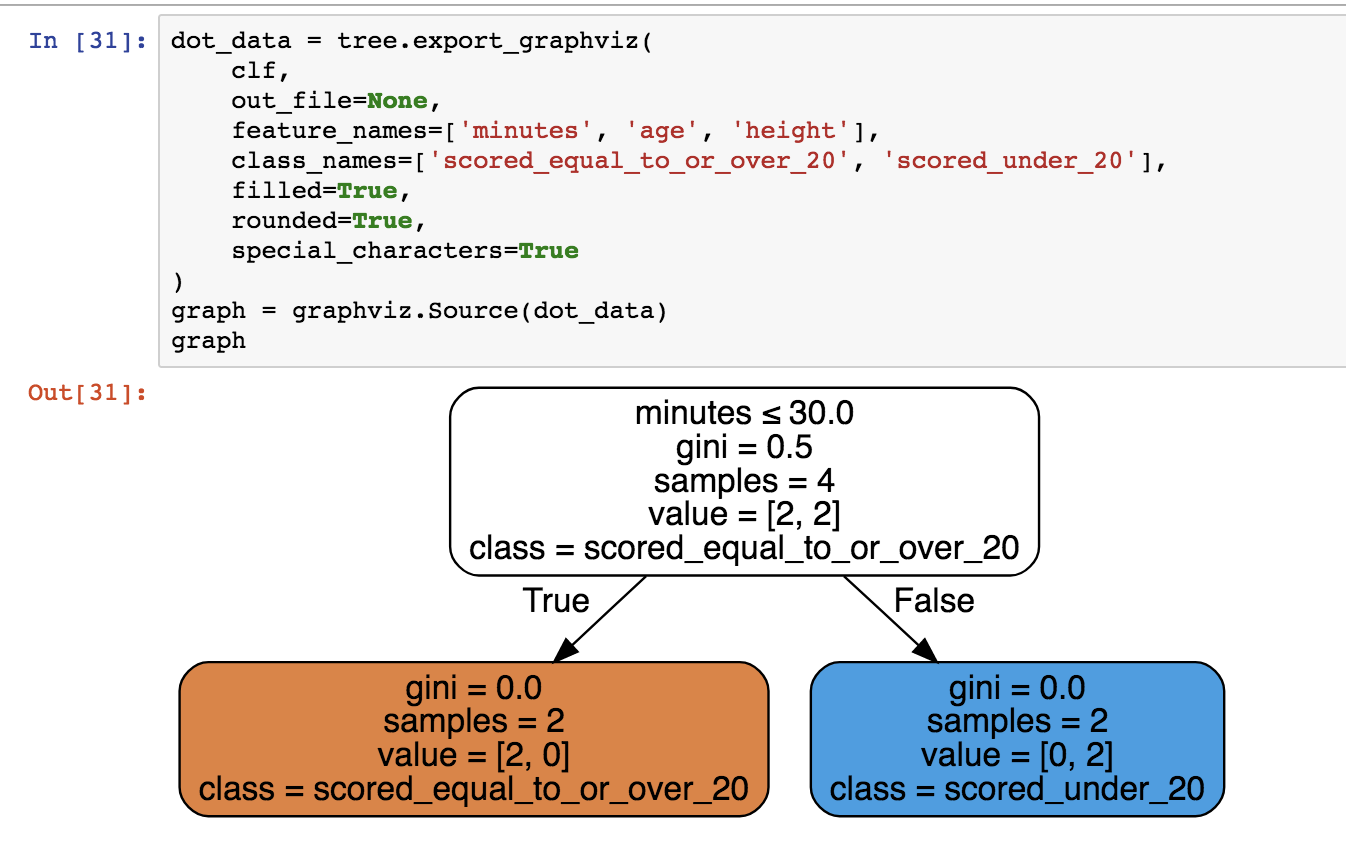

The decision tree correctly identifies that if the player players over 30 minutes a game, then they should score over 20 points (disclaimer: this is an unrealistic and oversimplified example). The graphviz package allows you to visualize this data:

The visualization confirms what we know to be true; if a player plays over 30 minutes, they scored over 20 points. The visualization also provides a good means to go over some terminology. The leaf nodes in the decision tree are the two child-most nodes that place a player in the > or < 20 point baskets; internal nodes are any non leaf nodes that divide up the data, excluding the top-most node in the tree, which is the root (note that this example is kind of contrived, since there is just a root node, two leaf nodes and no internal nodes).

How does DecisionTreeClassifier actually work under the hood? If you were to manually construct your own decision tree, you would have to select your own root and internal nodes. Those selections would be based on what features you believe to be most valuable in a data set; if you know that minutes are what matter most for player statistics, minutes will be the feature used at your root. In a real basketball data set, a natural starting question would be “Did the player play more than 0 minutes?” In the words of Google’s Josh Gordon, the best question is the one that reduces the uncertainty the most. If know the player did not play, I can claim with absolute certainty that they scored 0 points.

The decision tree algorithm makes feature selections like this based on criterion, which are used to compute the importance of each attribute and then arrive at the right questions to ask. While a human would anecdotally know that good NBA players get 30+ minutes a game, a decision tree would infer it statistically via criterion. I’m going to use Gini impurity as my criterion of choice here, since that is what DecisionTreeClassifier uses by default. This is actually configurable via the criterion parameter in sklearn:

criterion : string, optional (default=”gini”) The function to measure the quality of a split. Supported criteria are “gini” for the Gini impurity and “entropy” for the information gain.

Gini impurity, as the name suggests, is not a desirable quantity, and each node seeks to minimize it. Via Wikipedia:

Gini impurity is a measure of how often a randomly chosen element from the set would be incorrectly labeled if it was randomly labeled according to the distribution of labels in the subset.

This is a mouthful, so an example and some code should help. As noted in the wiki definition, Gini impurity is a probability, so its value must be between 0 and 1. If our data set has six players who all scored over 20 points, then only one label exists in the data set, so randomly guessing that label will be correct 100% of the time. Gini impurity is 0, since we’re never wrong. However, if three players scored less than 20 and three scored more, than guessing > 20 would be right half the time, and wrong half the time (as would be < 20). Gini impurity is 0.5 since we’re wrong half the time.

Josh Gordon implements gini in the following way, and the two examples work using it:

A decision tree algorithm will construct the tree such that Gini impurity is most minimized based on the questions asked. You can actually see in the visualization about that impurity is minimized at each node in the tree using exactly the examples in the previous paragraph; in the first node, randomly guessing is wrong 50% of the time; in the leaf nodes, guessing is never wrong. When the data makes perfect sense, so does the tree.

Unfortunately, data is inherently messy, and configuring the tree to work based on the data will be a subject of a future post.

Note that the sklearn source here is pretty difficult at least for me to parse (interesting note - the base class BaseDecisionTree is also the parent of DecisionTreeRegressor, which can be used to make floating point number predictions and may be the subject of a future blog post), so I turned to documentation and other writing for the explanations in this blog post. Here’s a summary of the most useful ones I found:

- sklearn docs

- Victor Lavrenko lecture

- Josh Gordon, Decision tree classifier from scratch

- Josh Gordon Jupyter notebook with tree from scratch

You can find all the code from this post in this Jupyter notebook.